02

Air temperature

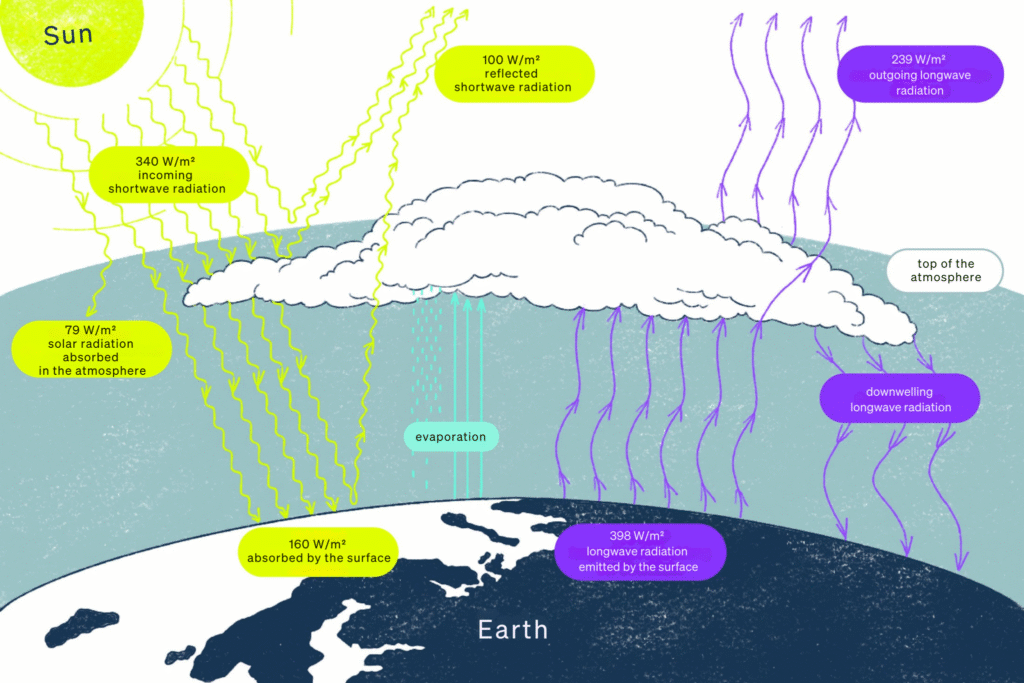

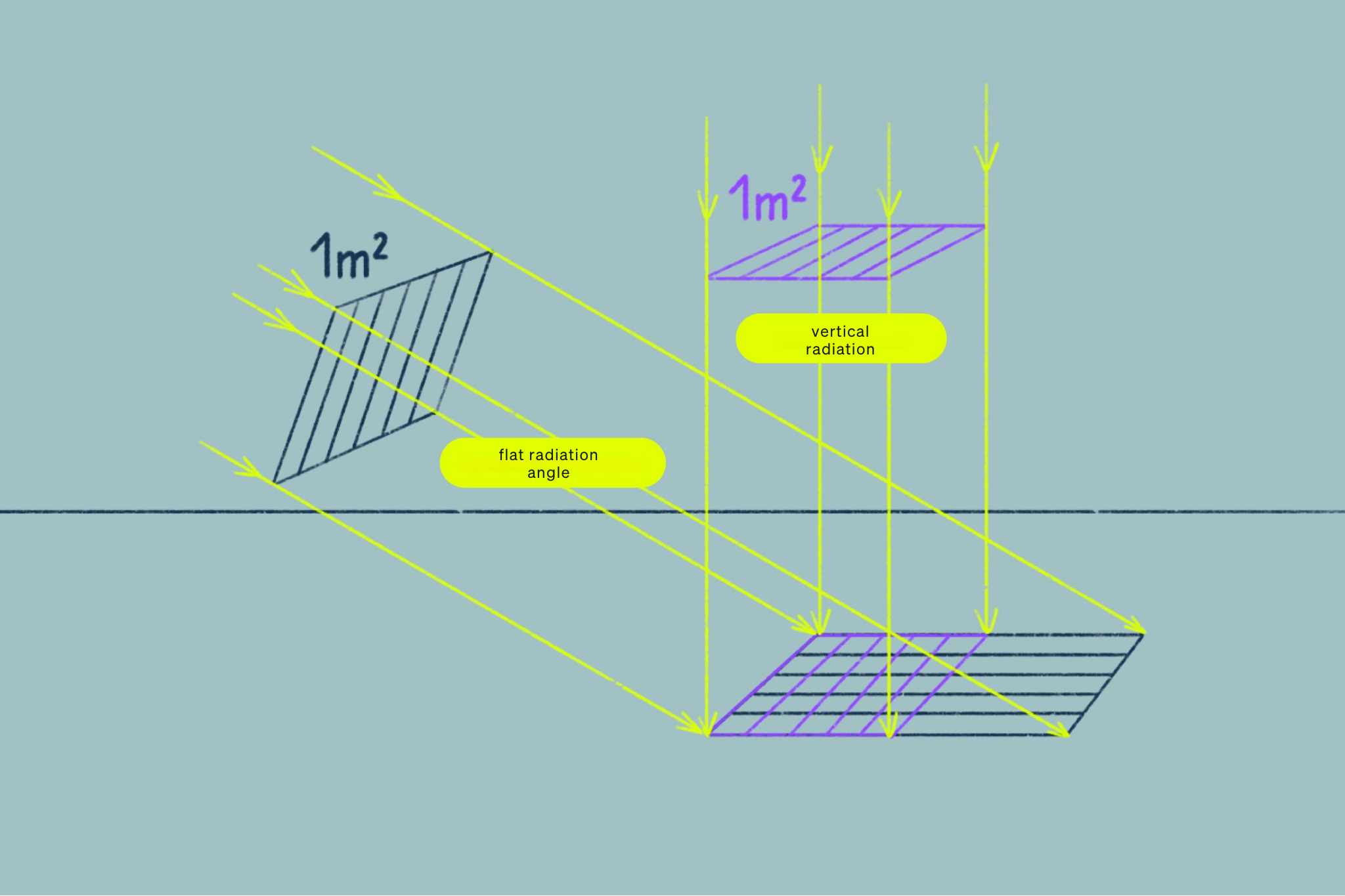

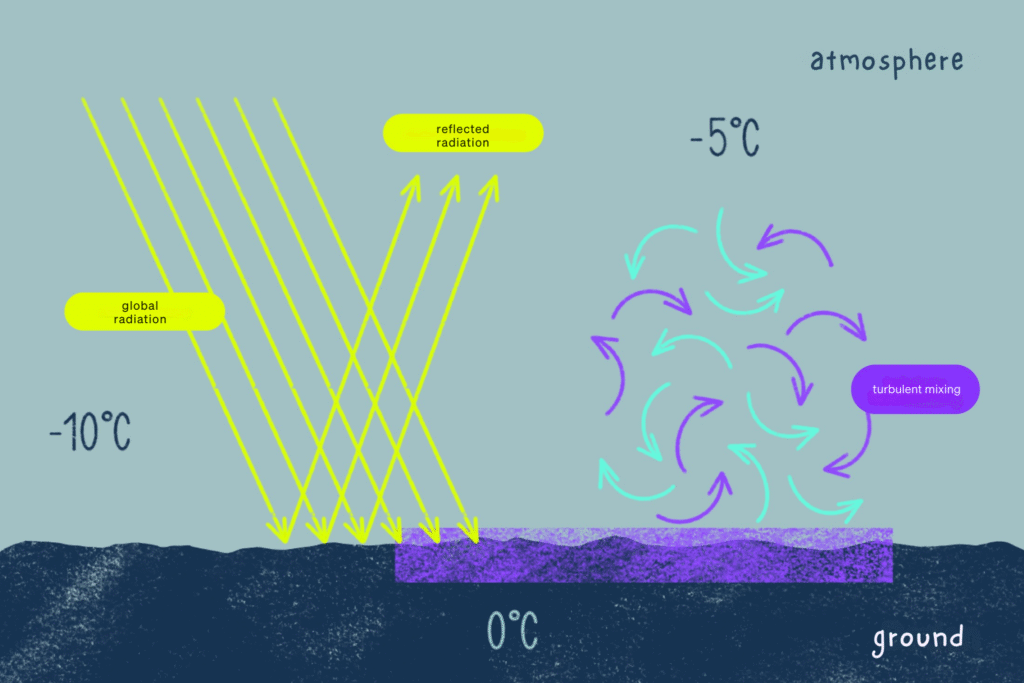

The air temperature is a measure of the heat content of the air. The air is not heated directly by solar radiation, but indirectly by the long-wave rays emanating from the ground and by the process of turbulent mixing. This means that when solar radiation hits the ground – grass, forest, rock, etc. – it heats up. The lowest layer of air (a few millimeters) is then heated by thermal conduction. Through small-scale, turbulent eddies, this heated air mixes with the layer of air above. As this process takes time, the highest temperature is not measured at the same time as the highest position of the sun, but with a time delay of two to three hours after midday.

The air temperature is always measured two meters above the ground and protected from radiation (in the shade) and is given in degrees Celsius (° C), Kelvin (K) or Fahrenheit (F). In principle, the higher the air pressure, the higher the temperature – and as the air pressure is highest at sea level and decreases with altitude, the temperature also decreases with altitude (vertical temperature gradient). The decrease in temperature with altitude is usually around 0.65 °C per 100 meters of altitude. In very dry air, it can even be up to 1 °C per 100 meters of altitude.

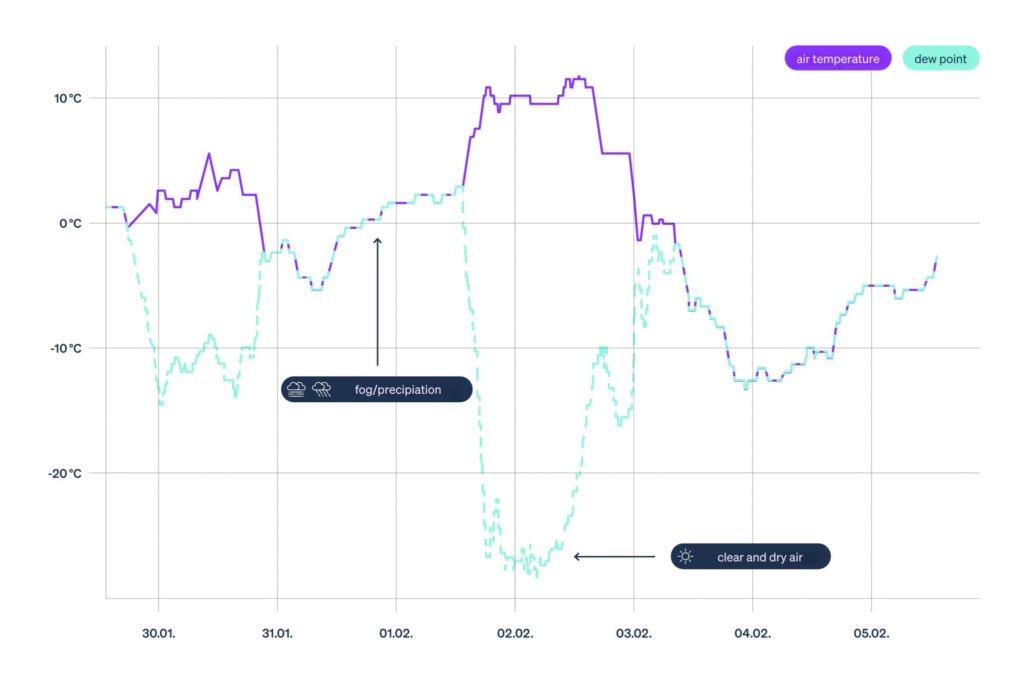

The distribution of air temperature plays a special role in inversion weather conditions. The higher layers of air are then warmer than the lower ones. This inversion weather situation often occurs in the fall and winter months when cold air collects in valleys and lowlands. It is then cloudy and cool in the valleys, but sunny and mild in the mountains. An inversion weather situation can be very persistent during winter high-pressure conditions.

Note: It’s a good idea to take a look at the webcam to get a better idea of the conditions on the mountain.

03

Air pressure

Air pressure is the weight of air on a certain surface. It is given in hectopascals (hPA) or millibars (mbar) (1 hPa = 1 mbar). Air pressure decreases with altitude. The average air pressure at sea level is 1013 hPa, which corresponds to the pressure of a 10 m high water column. For forecasts and analyses, meteorologists usually use the sea level at which the air pressure is 850 hPa, which is approximately the case at an altitude of 1500 m above sea level. However, air pressure is not only dependent on altitude, but also changes horizontally. The large-scale air pressure distribution determines the current weather situation, which is why weather changes are often associated with changes in air pressure.

Decrease in air pressure with altitude:

At high altitudes, above 2,500 m, the air pressure decreases exponentially. This means that there are fewer air particles in the same amount of air that we breathe in. Our body therefore has to work harder (including breathing faster and deeper) to absorb the required amount of oxygen. The thin air can be unpleasant for people. Altitude sickness with shortness of breath, headaches, nausea, insomnia etc. can be the result from an altitude of around 2,000 to 2,500 meters. Through appropriate acclimatization, the body can slowly adapt to an altitude of up to approx. 5,300 m, above which it is no longer possible to stay permanently. Climbing the highest mountains above 8,000 m is possible without oxygen, but the vast majority of expedition participants use oxygen, which they carry in bottles and breathe through a mask from a certain altitude and depending on the effort.

High pressure areas and low pressure areas

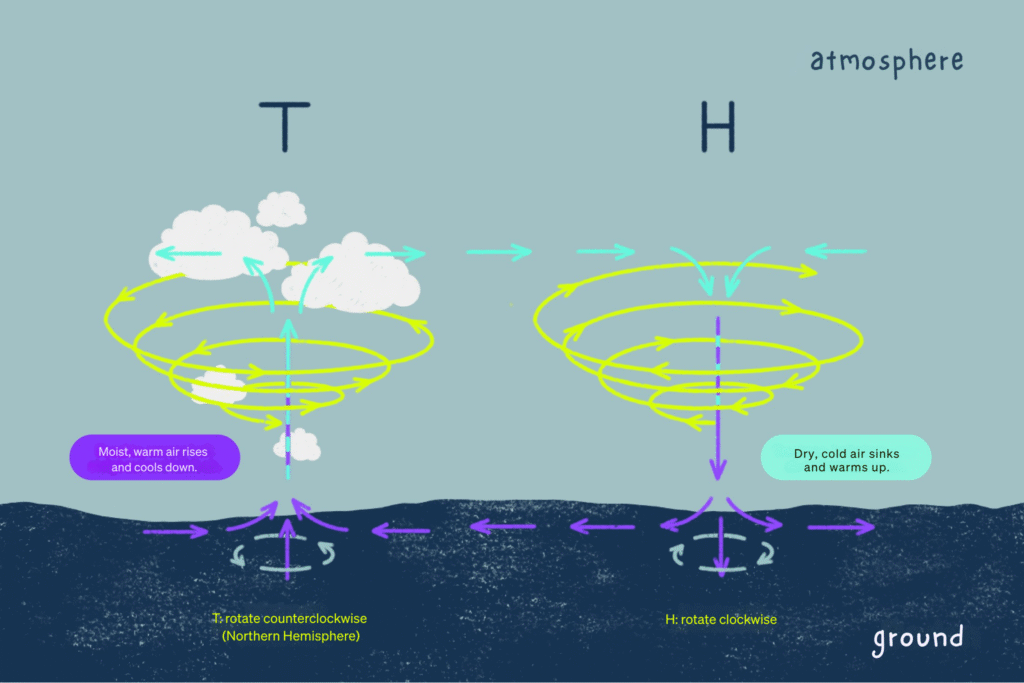

Low pressure areas form when the air is heated by solar radiation. Heated air expands, has a lower density compared to its surroundings and rises. As the air masses heat up, more water vapor can be absorbed and transported upwards. This results in the formation of clouds as the air cools down. This is why low-pressure areas are often associated with cloudy and rainy weather.

High pressure areas form when cold air masses sink due to a higher density. High pressure areas are often associated with fair weather, as the air is dried/heated as it sinks and clouds disperse.

The position of high and low pressure areas determines the weather situation.

04

Wind

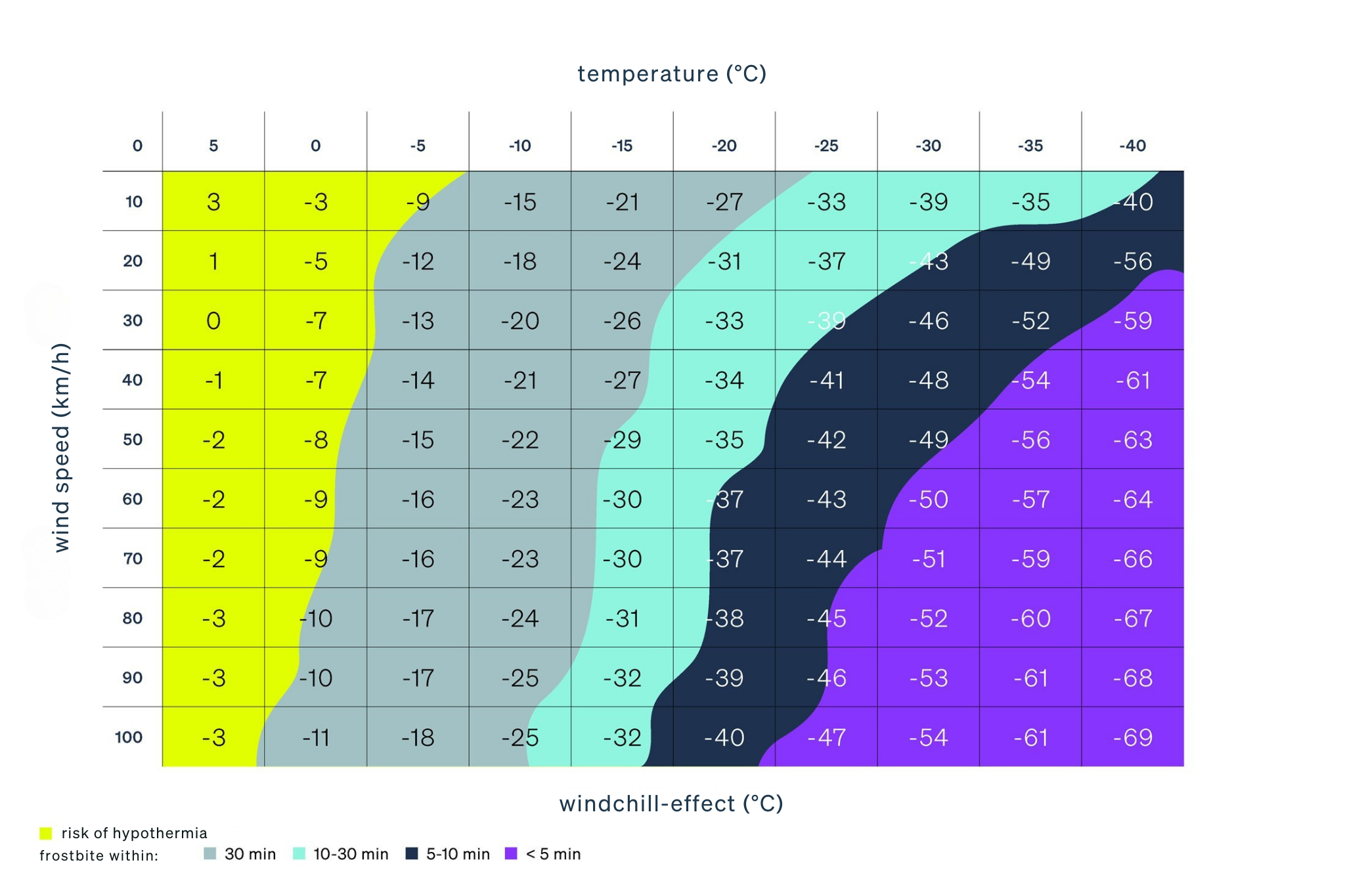

On the mountain, wind can very quickly become unpleasant and – especially in winter – sometimes even dangerous. Wind causes the perceived temperature to be colder than the air temperature (see wind chill effect) and the body cools down more without appropriate protection.

Strong winds (from approx. 40 km/h) can set large objects in motion and throw people off balance. If you are in rough, difficult terrain in such wind peaks, it can quickly become dangerous.

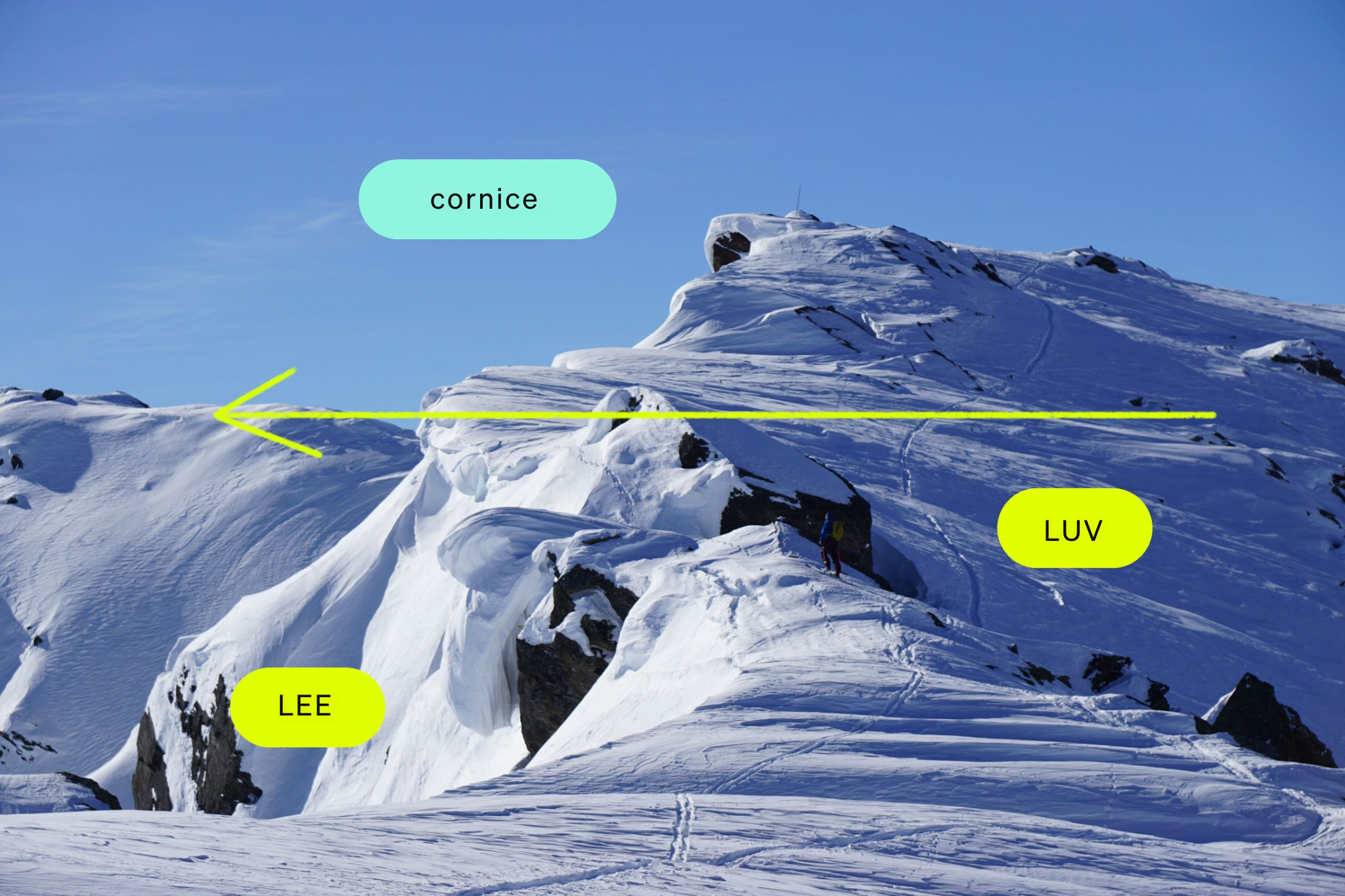

Wind also plays a decisive role in avalanche risk; it is even referred to as the “master builder of avalanches”, as it is responsible for the formation of drifting snow that is suitable for snow slabs. Such transported snow is already possible from a wind speed of approx. 15 km/h.

Incidentally, the wind direction always indicates where the wind is coming from. A westerly wind, for example, comes from the west and a mountain wind blows down from the mountain.

If the snow is only transported by the wind close to the ground, it is referred to as drifting snow. If this impairs visibility – i.e. if the swirling snow is at eye level or above – it is referred to as blowing snow.

How is wind created?

A key factor in the formation of wind is the heating of the earth’s surface and the surrounding air by the sun. Heated air rises upwards and cools down. In colder areas, cold, dry air masses sink downwards. This results in a distribution of different air pressures. To equalize these differences in air pressure, the air flows from the areas with high air pressure to those with lower air pressure. This causes the layers of air to move – the result is wind. Colder air flows to where warm air rises.

Influence of mountain surfaces (relief) on the wind

The wind speed increases with altitude due to ground friction, which is why it is generally windier on the mountains than in the valleys. An exception to this are some passes and notches, where the so-called jet effect can ensure that it is windier there than on the peaks. This happens because the wind tries to flow around obstacles such as mountains and seeks lower passages (passes, notches).

Due to their relief and exposure, mountains can have different effects on the wind. For example, the mountains can accelerate and deflect the wind, as well as disrupt its laminar flow, creating turbulence. For this reason, the main wind directions at higher altitudes in the mountains can also differ from the winds predicted in the weather forecast in valley systems.

Valley constrictions lead to a higher velocity of the air flow. If the wind blows through a constriction (e.g. narrow valley section), the flow lines at the entrance are compressed at right angles to the direction of flow, resulting in compression of the air (and thus an increase in air pressure).

At higher altitudes above the ground, the air flow is normally laminar, i.e. uniform. However, the air flow can become turbulent due to the uneven surfaces of mountains. When winds encounter obstacles such as mountains, the wind speed decreases on the downwind side (lee side). At this point, vortices repeatedly form in the air flow. These vortices can manifest themselves in the form of sudden gusts of wind. Although the wind speed is lower on the lee side than on the windward side (windward side), an increased gustiness occurs there.

The wind direction always indicates where the wind is coming from, for example a westerly wind comes from the west and the mountain wind blows down from the mountain.