Risk assessment and decision-making when freeriding

06.09.2023

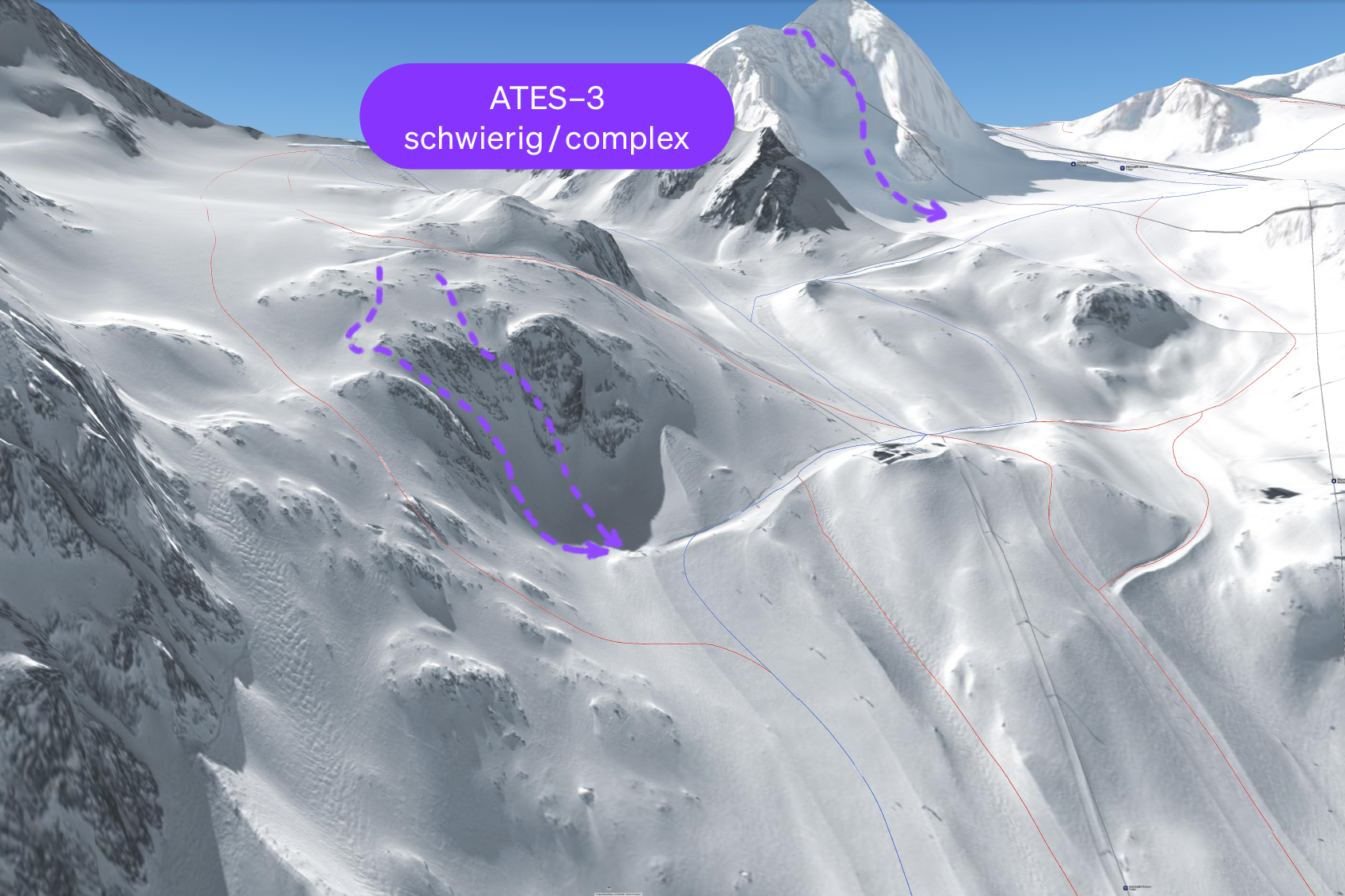

When deciding whether a freeride run is possible or not, a basic understanding of what makes a descent dangerous is crucial. Every freerider can and must decide for themselves what risk they ultimately take – i.e. whether to ride or not.